Nitroglycerin Drips & CHF Management

Introduction

As EMS progresses into the world of prehospital IV pumps, nitroglycerin drips throughout transport are becoming more common over continuous sublingual doses. In this article, we will explore the basic pathophysiology of nitroglycerin, why drips may be better than standard applications of nitroglycerin, and their use in CHF/SCAPE scenarios.

CHF Basics - Patho

Congestive heart failure, as the name suggests, is a failure of either side of the ventricles to pump effectively resulting in systemic or pulmonary congestion. When we speak of congestive heart failure in emergency medicine, we are most commonly referring to left ventricular heart failure which poses the highest risk of acute life threat.

Understanding left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)is critical to understanding the pathophysiology of CHF. Left ventricular ejection fraction is described as a percent and measures the percent of blood outflowed through the left ventricle with each contraction of the heart. In other words, it measures stroke volume compared to the total volume remaining in diastole. (Kosaraju et al., 2023). Congestive heart failure is a condition of insufficient ejection fraction leading to a backup of blood throughout other parts of the body, notably the lungs and areas of the body that are gravity dependent such as the sacrum and lower extremities. Blood has to go somewhere, and if it’s not leaving to systemic circulation via the aorta then it will back up through the circuit of the heart upwards.

As the LV fails to eject a sufficient amount of blood with each contraction, blood continues to flow into the atria and down into the ventricles from the lungs. This backflow returns fluid to the lungs and causes pulmonary edema (with the majority of the edema being the plasma of the blood itself). High pressure exacerbates the amount of and the force of the plasma moving into the alveoli. Excess fluid drowns the alveoli that would normally allow for gas exchange prompting hypoxia. This is the major pathophysiology involved when we manage CHF in the field and in the emergency department.

A failure of the left ventricle to adequately pump causes global hypoxia and a positive feedback loop that ultimately worsens CHF. As the body becomes hypoxic, vasoconstriction occurs as a means to raise blood pressure and correct hypoperfusion. Hypoperfusion also triggers the RAAS system of the kidneys, prompting fluid retention and worsening vasoconstriction. This worsening vasoconstriction in turn worsens hypoperfusion and increases afterload, forcing the heart to strain against even greater resistance as it struggles to meet demand.

Preload, put simply, is the volume of blood returned to the heart that the heart must then pump out. Afterload is the systemic resistance of the vascular space. In order for blood to actually flow out of the aortic valve, the force generated within the left ventricle must overcome the systemic vascular resistance (the afterload) to open it. As CHF progresses, afterload (the resistance) increases to compensate for poor perfusion - but this also forces an already weak heart to work harder and produce higher pressures to maintain perfusion.

CHF Basics - Classic Acute Management

Management of CHF exacerbation involves two major components - respiratory support and preload/afterload reduction. By reducing the amount of fluid volume returning to the heart in addition to reducing the work required of the heart to provide perfusion to the rest of the body, we can reduce cardiac workload overall and resolve distress. Of course, we need to avoid hypoxia in the meantime - so that’s where supplemental O2 and NIPPV comes in.

As stated above, these patients will develop their own positive feedback loop that will ultimately worsen their heart failure if left uncorrected. We accomplish this primarily through vasodilators such as nitroglycerin and through the use of positive pressure ventilation to correct hypoxia while also reducing preload (and thus afterload).

CPAP/BiPAP - Humans typically breathe via negative pressure - that is, our diaphragm contracts downwards, creating a vaccuum of potential space within the lungs to draw air in. Air will always follow the path of least resistance, and the pressure in our lungs becomes lower than atmospheric pressure when we breathe in. Positive pressure ventilation flips this pathophysiology and instead forces air directly into the lungs. By forcing air in the lungs, we increase the intrathoracic pressure and thus actually compress the great vessels and the heart in the process. By doing this, we are reducing the amount of preload that is returned to the heart. We are also correcting their innate hypoxia by providing supplemental O2. Positive pressure ventilation also helps open collapsed alveoli that would otherwise be drowned in pulmonary edema.

Nitroglycerin is one of main pharmacologic ways that we reduce preload. It is most commonly applied via sublingual tablets or spray in addition to nitroglycerin paste applied for longer effect. Nitroglycerin is a rapid-acting nitrate with a short duration of effect.

Diuretics are the definitive treatment for hypervolemic CHF exacerbation as they work by correcting the actual underlying problem. Diuretics cause the body to dump fluid by way of the kidneys in order to reduce the amount of circulating volume and thus reduce preload. These are most effective when given in the moderate to long term; patients will often be admitted to the hospital for several days to allow for full diuresis when they become severely hypervolemic. Common examples include furosemide and hydrochlorothiazide. Different classes of diuretics have different mechanisms, but most work by enacting some form of increased activity on the kidneys. For instance, furosemide and similar drugs (loop diuretics) work by increasing the action of the loop of Henle within the kidneys, thus allowing for more water and sodium loss as the kidneys filter.

Nitroglycerin Drips - Their Role in the Hospital and the Field

Nitroglycerin drips are commonly given in the hospital for patients with significant hypervolemia, hypertension, and progressed respiratory distress. Instead of producing one time doses of nitroglycerin like in tablet form, nitroglycerin drips allow us to set a specific, exact rate of nitroglycerin delivered per minute to maintain a titratable, longer duration of action and reduce preload over longer periods of time.

In my personal experience, nitroglycerin drips are used as a temporizing measure to reduce the overall BP as a means to reduce flash pulmonary edema while the patient also receives diuresis. As the patient has an overall loss in fluid volume, the nitroglycerin is titrated down and eventually trialed off. BiPAP patients with flash pulmonary edema often no longer require NIPPV after some time on both diuretics and a nitroglycerin drip in the ED. Long term nitroglycerin drips are not particularly common.

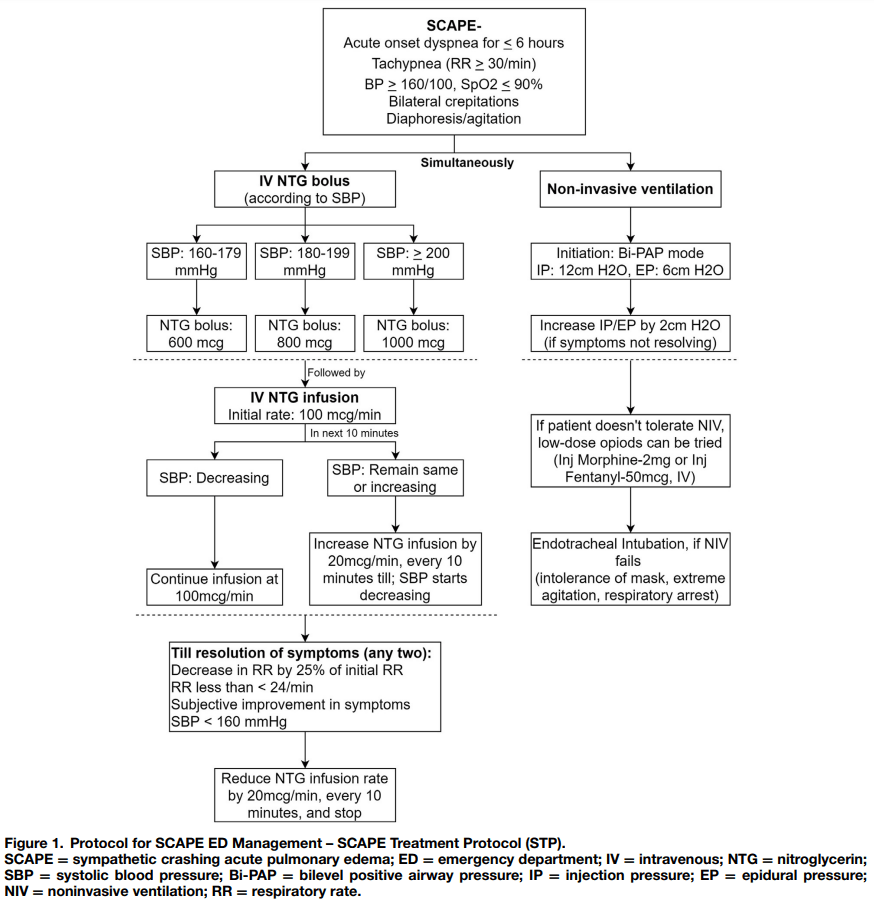

Example of a US ED SCAPE nitroglycerin drip protocol.

Typical infusion rates begin at 50-80mcg/min and titrate up to 400mcg/min (which is equivalent to giving one SL tablet each minute). Each hospital and EMS system may have a different infusion start and max, though. SBP <140mmhg is a common goal, but again infusion rates and goals can vary by EMS and hospital system protocols. With the prehospital realm, aiming for a higher SBP to give room for the ER to titrate and manage therapy more long-term may be appropriate.

The primary major risk of nitroglycerin infusion is hypotension. Patient can have varying responses to therapy and may require slower titration if they are more sensitive. What produces profound hypotension in one patient may induce minimal effect in another. An EMS trial of prehospital high dose nitroglycerin found a relatively small risk of hypotension with just 2 percent of included cases having any episode of hypotension during field care (Patrick et al., 2020). Nitroglycerin drips are already in regular use in EDs.

Nitroglycerin is a good “fast on, fast off” drug with a half life of roughly 4 minutes (Drugbank, n.d.). Nitroglycerin is renally excreted and can have a prolonged effect in patients with renal impairment (Drugbank, n.d.). As with any drug, discontinue infusion in the event of an adverse event such as hypotension. Nitroglycerin is known to build a tolerance in patients within hours of use and as such is not a good long term therapy for angina or hypertension (Kaesemeyer & Suvorava, 2022).

Conclusion

Nitroglycerin infusions offer a safe and effective means at reducing soaring hypertension as a bridge to diuresis in the setting of SCAPE/fluid overloaded respiratory patients. With EMS providers already familiar with and using nitroglycerin on a regular basis, early intervention with nitroglycerin infusions in the prehospital setting can help avoid respiratory needs escalation later on.

References

Drugbank. (n.d.). Nitroglycerin pharmacokinetics. Retrieved January 20, 2026, from https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00727

Jli. (2022, May 28). Article Bites #39: Prehospital IV bolus nitrogylcerin for pulmonary edema? An evaluation of feasibility, effectiveness and safety. NAEMSP. https://naemsp.org/2022-5-28-prehospital-iv-bolus-nitrogylcerin-for-pulmonary-edema-an-evaluation-of-feasibility-effectiveness-and-safety/

Kim, K. H., Kerndt, C. C., Adnan, G., & Schaller, D. J. (2023, July 31). Nitroglycerin. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482382/

Kosaraju, A., Goyal, A., Grigorova, Y., & Makaryus, A. N. (2023, April 24). Left ventricular ejection fraction. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459131/

Nickson, C. (2020, November 3). Afterload. Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. https://litfl.com/afterload/

O’Keefe, E., & Singh, P. (2025, January 1). Physiology, cardiac preload. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31082153/

Patrick, C., Ward, B., Anderson, J., Keene, K. R., Adams, E., Cash, R. E., Panchal, A. R., & Dickson, R. (2020). Feasibility, Effectiveness and Safety of Prehospital Intravenous Bolus Dose Nitroglycerin in Patients with Acute Pulmonary Edema. Prehospital Emergency Care, 24(6), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2020.1711834

Stemple, K., DeWitt, K. M., Porter, B. A., Sheeser, M., Blohm, E., & Bisanzo, M. (2020). High-dose nitroglycerin infusion for the management of sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE): A case series. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 44, 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.062