Essential Critical Care Medications, Vasopressors, Sedatives: A Review

Introduction

The emergency room is truly the catch-all department of the medical field, managing everything from runny noses and broken ankles to respiratory/cardiac arrest, ARDS, and severe traumas. Practicing in any role in emergency medicine requires a wide knowledge base, but critical care medicine is specifically where we can make the most impact and save the most lives. Whether you are a seasoned paramedic or a new grad nurse, this article intends to serve as a resource and refresher for the basic pathophysiology and use cases of the most common critical care medicines in use in the emergency department.

We will begin each section by discussing the overall class of medication and then exploring the most common medications in each class. We will primarily focus on sedative drips and vasopressors.

Vasopressors

Example scenario: 51yom patient presents to the ED by way of EMS after becoming increasingly altered and lethargic at his nursing home. Patient has a pertinent history of paraplegia, CVA, and is immobile by baseline with multiple recurrent pressure injuries from being bedbound. He is slow to respond and does not follow commands on arrival, with significant tachycardia and hypotension. After several rounds of fluid challenge, the patient continues to be tachycardic and hypotensive, and the decision is made to start a vasopressor for pressure support.

Cardiac Output

Cardiac output is the volume of blood pumped out by the heart in a minute. It is calculated by stroke volume (SV) x heart rate = total cardiac output. Stroke volume is the amount of volume pumped out with each contraction of the heart. While we can’t actually measure the exact cardiac output without invasive monitoring, understanding this idea can help us in titrating our medications and understanding what works best. Our goal with vasopressors is always to maximize cardiac output to maintain perfusion by altering some component of this formula.

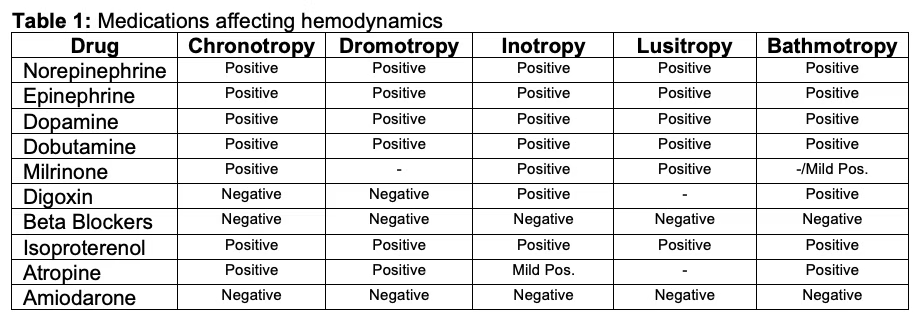

The Three Major Traits of Vasopressors: Chronotropy, Inotrophy, Dromotrophy

When we make the decision to provide a vasopressor, or really any kind of vasoactive medication, we are balancing the properties of chronotropy, inotropy, and dromotropy.

Chronotropy: Refers to the heart rate itself.

An example of negative chronotropy are beta blockers, which reduce the HR.

An example of an agent used for positive chronotropy is epinephrine, which raises the HR.

Inotropy: The strength and force of the heart’s contractions. Increasing contraction strength = raises stroke volume.

An example of an agent used for positive inotropy is epinephrine, which both increases HR and boosts the strength at which the heart contracts.

An example of an agent used for negative inotropy are beta blockers.

Dromotropy: Refers to the rate that impulses/excitation spreads through the conduction pathway of the heart itself. Does not work directly on the SA node (the “pacemaker” of the heart) but rather in the AV node primarily.

Not super relevant in vasopressors and in most of the common critical care medications we use.

Example: Adenosine has a negative dromotropic effect in that it slows conduction through the AV node as its primary mechanism of action.

Some medications work by having multiple properties. For example, epinephrine has both positive chronotropy and positive inotropy properties (often called a “true vasopressor”, with very little dromotropic action at all. Imagine us using these medications as tools to tug different aspects of physiology around.

Credit to FizzICU

Systemic Vascular Response (SVR)

Refers to the overall tone of the vasculature and plays a key role in afterload

Can actually be measured using invasive Swan Ganz monitoring

The degree of vasoconstriction present in the peripheral vasculature determines the degree of resistance that blood has to work against to move around the body

Higher SVR means that the vessels are “tighter” and thus more pressure is needed to overcome their resistance and flow

Lower SVR (like in vasodilatory shock) means that the vessels are too wide to actually help move flow along, and pooling occurs

When we use vasopressors, we are manipulating SVR in order to maintain perfusion

Other Terms to Understand

Blood Pressure: refers to the force against the arterial walls

Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP): refers to the average pressure throughout systole and diastole

We titrate commonly to a MAP goal of 60-65 at a minimum

This is thought to be the minimum to maintain cerebral and core organ perfusion for most patients (Yoshimoto et al., 2022)

Titrating to MAP is more common than titrating to a specific blood pressure

Someone can have an example blood pressure of 110/30 with a MAP of 57, even though their systolic is normotensive!

The Adrenergic Receptors

There are several main receptors that you should have knowledge of when working with critical care medications. With each receptor type, there are agonists that induce the main action of that receptor (they agonize it) and antagonists that block the action of that receptor (or stop the action of it).

Beta 1 Adrenergic Receptors: Beta 1 receptors primarily refer to the heart itself. Stimulation of beta-1 will also induce the RAAS as a secondary means of raising pressure.

Agonists will raise HR, induce positive chronotropy + inotropy, and raise blood pressure.

Antagonists (like beta BLOCKers) will lower HR and induce negative chronotropy + inotropy. This will lower blood pressure.

Beta 2 Adrenergic Receptors: Beta 2 receptors primarily work on the lungs and are not super relevant to most critical care medications.

Medications like albuterol are beta-2 agonists that induce bronchodilation and help increase overall air flow.

Alpha 1 Adrenergic Receptors: Primarily found in the smooth muscle of the vasculature.

Agonists will raise blood pressure by means of vasoconstriction.

Imagine two pipes, one that is very small and narrow and one that is wide and open. They have the same volume. Logically, pressure would be higher in a pipe that is more narrow with the same volume than a pipe that is wide open.

Examples of agonists: midodrine, phenylephrine (used in the ER/ICU sometimes, lots of anesthesia/OR use),

Antagonists not particularly common for critical care medicine.

Sometimes not ideal for use in critical care medicine as the alpha-1 agonists have an isolated effect on the vasculature.

Raising vascular tone and tightening the vessels increases afterload (the force that the LV works against) without providing inotropy to aid in overcoming that pressure demand.

Often used in isolated, known cause shock states such as neurogenic shock (totally vasodilatory) with an otherwise healthy cardiovascular system.

Alpha 2 Adrenergic Receptors: Primarily found centrally in presynaptic area of the neurons and have an opposite effect of alpha 1 receptors. Helps to mediate the release of norepinephrine.

Agonists will lower blood pressure and help inhibit the sympathetic nervous system (sympatholytic).

Examples include clonidine and dexmedetomidine (Precedex)

Antagonists not really used.

Medications

Norepinephrine

Naturally occurring catecholamine as part of the sympathetic nervous system

Usually the first line vasopressor for most shock states due to its support for hemodynamics without significant adverse effect

Primarily works on alpha 1 receptors (agonist) and beta 1 receptors (agonist) to induce action

Induces vasoconstriction and has a positive inotropic effect (raises contractility of the heart)

Limited effect on beta 2 agonists, does not commonly alter heart rate in most (Smith & Maani, 2024).

Can be ideal in patients at risk of tachyarrhythmias (like those that are already tachycardic; we don’t want to increase their rate further)

Dosing

Dosing is hospital and system-dependent

Commonly begins at 3-5 mcg/min, titrating up as accepted by policy to sustain hemodynamics

Risk of extravasation and tissue damage increases with higher doses

Epinephrine

The “true vasopressor”

Has positive chronotropic and inotropic effects

Raises HR, boosts contractility of the heart to raise blood pressure

Affects both SV and HR

Is a naturally occurring catecholamine in the body and is one of the main ways that the sympathetic nervous system enacts control over the body.

Dosing & Routes

0.3 to 0.5mg IM for anaphylaxis management

Can be dosed in micrograms in push dose format as a bridge to a vasopressor drip

Drips

Can be weight based or just straight dosing (mcg per min).

Typically 0.1mcg/kg/min to 0.5mcg/kg/min

Some use for epinephrine drips as first line in severe anaphylactic shock

Mediates the anaphylaxis itself as a means to reverse shock rather than merely supporting hemodynamics.

Vasopressin

Is an analogue to naturally-occurring antidiuretic hormone (ADH)

Helps retain fluid volume and thus avoid further loss/maintain pressures for perfusion

Works on V1 receptors to induce widespread vasoconstriction (Nickson, 2024)

Can be renal-supporting by vasoconstricting renal arterioles to boost perfusion, avoid kidney injury during shock states (Nickson, 2024).

Also stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release to boost cortisol as a means to respond to metabolic stress (Openanesthesia, 2025)

Classic specific use examples

Hypovolemic shock

Septic shock

ADH depleted (Openanesthesia, 2025)

Norepinephrine requirements are becoming excessive to maintain perfusing MAPs

Variceal bleeding

Massive source of blood, fluid loss

Is never a standalone vasopressor and acts as a supportive agent to other drips/medications

Typically last to add, first to wean off

Phenylephrine

Has mainly alpha 1 agonism properties

Causes direct vasoconstriction by acting on the smooth muscle of the vasculature without necessarily having any inotropic or chronotropic effects (Richards et al., 2023)

Is not commonly used for most shock states

Raising SVR (which is what alpha 1 agonism will do) while not providing any further cardiac support by way of inotropy or chronotropy can sometimes worsen ischemia

Making an already weakened and diseased heart force out against higher pressures isn’t ideal

Use case examples

Neurogenic shock is a vasodilatory state where the heart itself is not diseased and the body is often not under any other stressors besides the vasodilation itself

Phenylephrine can be useful in this instance

OR cases sometimes require phenylephrine pushes while under anesthesia

Cardiac surgeries

Post-RSI hypotension

Induction meds like etomidate are mostly sympatholytic, so phenylephrine can be a bridge to support hemodynamics until they wear off

Push dose pressors like epinephrine also used for this

Dobutamine

Positive inotrope, chronotrope medication that is primarily used in cardiogenic shock (Ashkar et al., 2024b)

Drops systemic vascular resistance, raises stroke volume all while often having little effect on end arterial blood pressure (Ashkar et al., 2024b)

Helps perfusion while not worsening the systolic dysfunction leading to poor perfusion in the first place

Beta 2 activation also causes peripheral vasodilation

Risk of prompting arrythmias

Particular risk for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response in patients with existing history of afib (Ashkar et al., 2024b)

Not often titrated, is often used on its own

Can be ideal for cardiogenic shock with CHF patient as traditional vasopressors like norepinephrine raise SVR, vasoconstrict -> worsens afterload -> increases ischemia and heart workload

Dobutamine avoids this vasoconstriction and increased afterload

Special Considerations with Vasopressors

Extravasation

Extravasation leading to tissue necrosis and damage is a major risk with any vasopressor medication.

When released into the tissues and interstitial spaces instead of the vascular space, localized vasoconstriction occurs -> local tissue ischemia results.

Antidotes exist, but have to be given quickly.

Because of the risk of extravasation, it is best to use central lines when using high doses of vasopressors.

However, peripheral IVs work in emergencies and sometimes at low doses without the need for central line placement (Loubani & Green, 2015).

Best practices

Avoid PIVs in areas with constant movement (such as the AC) or in small veins (such as the hand).

Use the largest bore PIV possible; 20g and larger preferable.

Higher risk of extravasation with smaller gauges.

Regularly reassess PIVs for signs of infiltration or impending dislodgement

Adding Vasopressors/Stacking

If a single agent (like norepinephrine) is requiring high doses to reach acceptable MAPs -> another vasopressor can be added to supplement

Nursing: Use the second pressor to try to decrease the dose requirement of the first pressor

Wean the first pressor down by titrating the second pressor up

With time, goal is to wean the second pressor back down -> discontinue it entirely

Our goal is always the best hemodynamics with the least amount of vasoactive medications possible

High doses of vasopressors bring their own risks of arrhythmia, extravasation, receptor oversaturation, etc.

IV Sedative Medications

After initial resuscitation, the above stated 51yom grows increasing tachypneic with refractory hypoxia and requires intubation. Intubation is done successfully with etomidate and succinylcholine. The patient is placed on a ventilator, but does show some signs of agitation and vent-bucking.

Sedation Basics

Adequate sedation not only helps us keep our patients manageable (not pulling at lines, not fighting the ventilator, etc) but also provides absolutely necessary patient comfort. Awake intubation is a terrible thing to experience, especially in the midst of resuscitation in a loud and stimulating emergency department, ICU, or ambulance.

One of the main struggles of adequate sedation is balancing the hemodynamic effects of sedation medications with what is necessary for sedating the patient.

Receptors

GABA

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain

Plays major roles in mood, consciousness, memory

Fun fact: Alcohol works on this receptor, hence “blacking out” amnesia and poor memory with chronic alcoholism

Major role in seizures

GABA “opposes” the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate

Alcohol withdrawal is a state of profound GABA insufficiency -> glutamate becomes dominant -> seizures occur

Major oversimplifcation but that’s the summary

Alpha Receptors

Alpha 2 Adrenergic Receptors

Agonism of alpha-2 receptors not only produces vasodilation, but some degree of sedation

Both peripheral, central receptors are present

Peripheral vasodilation, some CNS depression

Examples of meds that work this way include clonidine, precedex

Sedative Medications

Midazolam

Benzodiazpine that is commonly used for emergent seizure control, agitation sedation, RSI and post-intubation sedation

Works on GABA receptors; GABA agonist

Risk for respiratory depression as a result of CNS depression in patients without a definitive airway

Commonly given via IV push

Can be given IM or IN

Drips sometimes used, but moreso in the ICU setting and not commonly

Dosing

Typically 0.1mg/kg, up to 2mg IV

Often just dosed at 2mg

IM/IN 5mg

Repeat until desired effect

Propofol

Potent sedative medication that is commonly used as part of RSI, procedural sedation, and post-intubation sedation

Is the drug of choice for continuous drip post-intubation sedation

Works by decreasing release of GABA from bound receptors in the brain (Folino et al., 2023)

Works on GABA similar to benzodiazepines

Considerations

Major risk for hypotension due to widespread vasodilation

Avoid in hemodynamically unstable patients

Can use push dose or drip pressors to buy a “buffer” in blood pressure before giving propofol or titrating up

Long term use risks include propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS) usually within 4 days (Folino et al., 2023b)

HyperK, acidosis, hyperlipidemia (Folino et al., 2023b)

High mortality

Has no analgesic effects

Requires adjunct analgesia for intubated patients

Seizure use

Can be used for cessation of status epilepticus seizures at high doses (Kim et al., 2024)

Can be given IV push or by a drip

IV push common for procedural sedation

Drips for post-intubation sedation

Dosing

Weight based

Typically 4-12 mg/kg/hr (Nickson, 2024a)

Can titrate up as needed to induce sedation

Dexmedetomidine (Precedex)

Alpha 2 agonist that is commonly used as an alternative to other sedation medications, namely propofol

Unique in that it does not induce respiratory depression like propofol or other medications

Sympatholytic sedative medication

Additionally has some degree of analgesic properties

Can reduce amount of opioids required in intubated patients

Has uses in both anesthesia and in critical care/ICU settings

Considerations

Risk for bradycardia

Sympatholytic effect, vagal tone increase -> possible bradycardia and hypotension (Pöyhiä et al., 2022)

Also risk for reflex hypertension (Pöyhiä et al., 2022)

Use a slow loading process

Do not escalate dose rapidly

Dosing

0.2 to 0.7 mcg/kg/hr commonly for drips (Reel & Maani, 2023)

SLOW titration

References

Ashkar, H., Adnan, G., Patel, P., & Makaryus, A. N. (2024, February 23). Dobutamine. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470431/

Folino, T. B., Muco, E., Safadi, A. O., & Parks, L. J. (2023b, July 24). Propofol. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430884/

Kim, E. D., Wu, X., Lee, S., Tibbs, G. R., Cunningham, K. P., Di Zanni, E., Perez, M. E., Goldstein, P. A., Accardi, A., Larsson, H. P., & Nimigean, C. M. (2024). Propofol rescues voltage-dependent gating of HCN1 channel epilepsy mutants. Nature, 632(8024), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07743-z

Kumar, S. (2023). Unraveling the role of antidiuretic hormone (ADH): from water balance to neurological signaling. Journal of Biochemistry Research, 82–86. https://www.openaccessjournals.com/articles/unraveling-the-role-of-antidiuretic-hormone-adh-from-water-balance-to-neurological-signaling.pdf

Li, L. Z., Yang, P., Singer, S. J., Pfeffer, J., Mathur, M. B., & Shanafelt, T. (2024). Nurse burnout and patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of care. JAMA Network Open, 7(11), e2443059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43059

Loubani, O. M., & Green, R. S. (2015). A systematic review of extravasation and local tissue injury from administration of vasopressors through peripheral intravenous catheters and central venous catheters. Journal of Critical Care, 30(3), 653.e9-653.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.01.014

Nickson, C. (2024a, July 13). Propofol. Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. https://litfl.com/propofol/

Nickson, C. (2024b, July 13). Vasopressin. Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. https://litfl.com/vasopressin/

Openanesthesia. (2025, August 20). Vasopressin. OpenAnesthesia. https://www.openanesthesia.org/keywords/vasopressin/

Pöyhiä, R., Nieminen, T., Tuompo, V. W. T., & Parikka, H. (2022). Effects of dexmedetomidine on basic cardiac electrophysiology in Adults; A descriptive review and a prospective case study. Pharmaceuticals, 15(11), 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15111372

Reel, B., & Maani, C. V. (2023, May 1). Dexmedetomidine. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513303/

Richards, E., Lopez, M. J., & Maani, C. V. (2023, October 30). Phenylephrine. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534801/

Smith, M. D., & Maani, C. V. (2024, December 11). Norepinephrine. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537259/?report=printable

Yoshimoto, H., Fukui, S., Higashio, K., Endo, A., Takasu, A., & Yamakawa, K. (2022). Optimal target blood pressure in critically ill adult patients with vasodilatory shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 962670. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.962670